Within the IT, Electronic Commerce and Consumers practice area, the Costaș, Negru & Asociații team today addresses a topic of maximum interest regarding the E-Commerce Directive.

I. Introduction

The new economic climate has been influenced by the rampant development of digitalisation in the century, as new variants and forms of business have appeared. If traditionally, the commercial relationships had a mostly local dimension, as merchants would usually engage in commercial relationships with other merchants or consumers in their proximity, digitalisation has extended the borders and allowed them to conclude cross-border transactions, through online platforms. Given that the Internet is a borderless medium, a regulatory framework regarding electronic commerce was necessary.

The E-Commerce Directive[1] comes as a normative support for streamlining electronic commerce and the proper functioning of the internal market. The purpose of this Directive is to create a legal framework to ensure the free movement of informational society’s services between Member States and to also guarantee the legal certitude of electronic commerce, while also increasing the consumers’ trust.

In the joined cases no. C-662/22 and C-667/22, The European Court of Justice tackles an essential issue for online services, especially intermediation ones: their free movement. In this specific case, The Court analyses whether Member States are allowed, by virtue of the E-commerce Directive, to impose additional reporting obligations for legal persons which provide this type of services.

II. Case summary

- Factual background

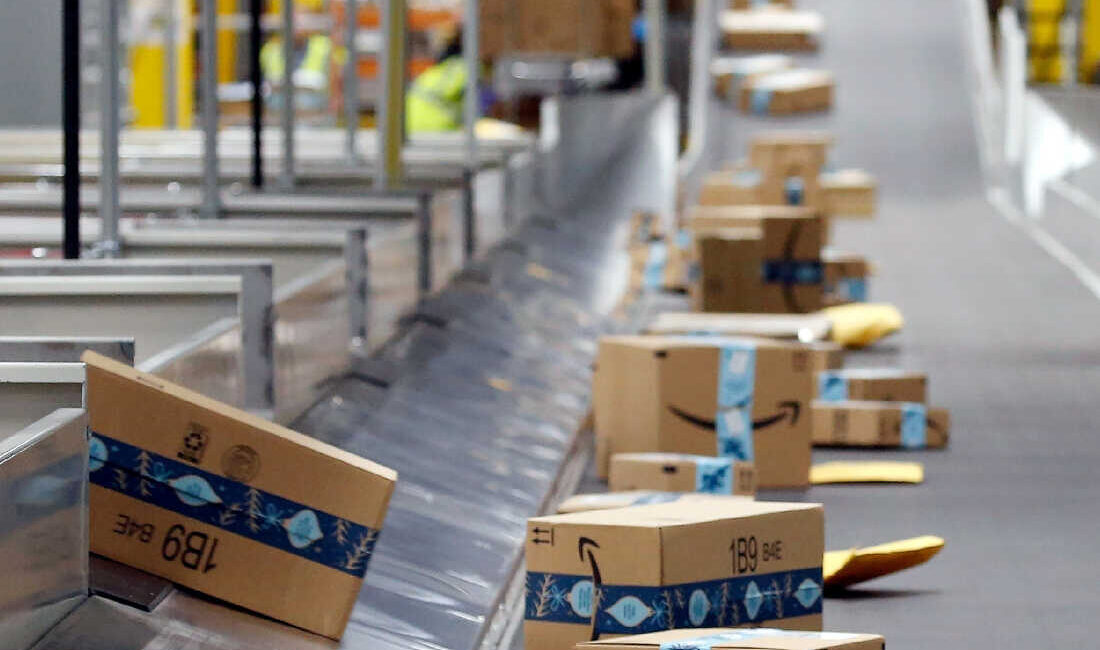

Airbnb, with its registered office in Ireland, and Amazon, with its registered office in Luxembourg, are online intermediary services platforms, whose activities are concentrated in different industries: Airbnb is active in the accomodation services industry and Amazon in the sales industry. In essence, their activity consists in the facilitation of direct transactions between the companies which offer certain services and consumers. The intermediation is based on a contractual relationship between the company which provides the service and the online intermediation platform.

The Italian national legal framework has been enriched with a new legal act, for the transposition of the Regulation (EU) 2019/1150 of the European Parliament and the Council regarding promoting fairness and transparency for business users of online intermediation services, through which a new obligation for the business users has been implemented. Essentially, business users are now required to enrol in a register which is administered by AGCOM (Communications Regulatory Authority) and to pay a financial contribution to cover the administrative costs incurred in the exercise of AGCOM’s functions. The business users are bound by this obligation, even if they are not established in Italy, as long as they provide online intermediation services on the Italian territory.

The purpose of this register is to collect information pertaining to the business users, in order to promote transparency amongst online intermediation services providers. The information which is required to be communicated concerns, inter alia, the share capital, names of the shareholders and their respective shareholdings with voting rights etc. Additionally, this information has to be updated on an annual basis.

In the event of non-compliance with the measures enshrined in this regulation, the person concerned would have a fine imposed on it of between 2-5% of that person’s turnover in the last financial year for which the accounts have been closed.

Consequently, Airbnb and Amazon have challenged this legislative measure before Regional Administrative Court of Lazio. They have argued that the new obligations may be contrary to the freedom to provide services, to Regulation 2019/1150 and to several directives. Additionally, the claimants have argued that they are mainly bound by the legal system of the Member State in which they are established. As a result, the referring court has addressed five preliminary questions to the European Court of Justice, which essentially question whether EU Law precludes a national provision which, albeit with the purpose of promoting fairness and transparency among providers of online intermediation services, imposes the obligation to enter a register for communicating information pertaining to a provider of online intermediation services, which may have an effect on the free movement of services.

The European regulatory norms which were mainly analysed were the Directive 2000/31 regarding electronic commerce and Regulation 2019/1150 regarding transparency for business users of online intermediation services.

- Judgement of the European Court of Justice

The Court has analysed the first, the third and the fourth questions within the same context, given that they tackle the de plano compatibility of a similar measure as the one in this with the e-Commerce Directive, as it is applied to business users which provide such services on the territory of another Member State than the one where they are established. The second and the fifth questions were implicitly answered to in the context of the Court’s arguments.

According to the Court, by virtue of Article 3 paragraph 4 of the E-Commerce Directive, Member States can adopt derogatory measures from the principle of free movement of information society services, which pertains to the coordinated domain, only in certain circumstances. The ”coordinated field” is defined by Article 2 let. H) as covering all the requirements established in Member States’ legal systems applicable to information society service providers or information society services, regardless of whether they are of a general nature or specifically designed for them. In other words, the coordinated field imposes requirements which the economic operator must fulfill and which regards the access for a services provided by the information society service provider (e.g. the requirements in the field of qualification, authorisation or notifications) and the provision of such service (e.g. the quality or the object of the service). Consequently, Directive 2000/31 is guided by the principle of control in the home Member State and mutual recognition, as a result information society service providers are regulated by the home Member State, as they possess exclusive competence in this domain.

However, given the mutual recognition principle, the Member State of destination of such services is obligated not to restrict the free movement of information society services. Therefore, ”Article 3 of Directive 2000/31 precludes, subject to the exemptions authorised under theconditions laid down in paragraph 4 of that article, a provider of an information society service wishingto provide that service in a Member State other than that in which he or she is established from beingsubject to requirements in the coordinated field imposed by that other Member State”. Contrary to the arguments set forth by the Italian Government, even though in reality, the reporting obligations did not necessarily tackle the access to provide these services, as its purpose was to facilitate AGCOM’s endeavours in supervising the providers’ activities, the Court has held that it is irrelevant if de facto, these economic operators could have effectively conducted their intermediaton activities, for imposing such an obligation, which mainly targets the providers whose places of establishment are in another Member States, is in itself a requirement which conditions.

Furthermore, the Court has verified the applicability of Article 3 paragraph 4 from the E-commerce Directive in the present case, which allows Member States to adopt derogatory measures from the principle of free movement of services. The Court observed that this norm regards „a certain service provided by the informational society provider”, therefore the Directive does not allow Member States to adopt ”general and abstract measures aimed at a category of given information society services described in general terms and applying without distinction to any provider of that category of services” (C-372/22, EU:C:2023:835, Google Ireland and others). In the present case, it seems that the measures have a general applicability, therefore they do not fall within the notion of measures regarding „a certain service of the information society provider”, according to the meaning of Article 3 paragraph 4 of the Directive 2000/31.

Additionally, the adopted measures must be necessary in order to ensure public order, the protection of public health, public security or consumers’ protection. Given that the Italian Regulation’s purpose was to transpose the Regulation 2019/1150, the Court has proceeded to peruse the purpose of the aforementioned Regulation and its possible compatibility with the purposes which are exhaustively mentioned in the E-commerce Directive. Lecturing Recitals (7) and (51) of the Regulation 2019/1150, its purpose is to establish a set of binding norms which promote an equitable, predictable, durable and fiable business environment for online commercial transactions. Therefore, the European Court of Justice has held that, on one hand, there is no direct connection between the purposes of these European regulations, and on the other hand, the purpose of the Regulation 2-2019/1150 does not concern neither the protection of public health, nor public security. Moreover, it also does not cover consumers’ protection, as the Regulation is mainly targeted towards economic operators and it regulates the relationship between online intermediation service providers and the user companies. The Court has finally reiterated that Article 3 Paragraph 4 of Directive 2000/31 is to be strictly interpreted and it cannot be applied to measures which are susceptible to possess an indirect link at most with one of the purposes envisaged in its content. In conclusion, the national measures adopted by the Italian regulators are not covered by Article 3 of the Directive.

III. Conclusion

Although the Internet seems to be a borderless space, companies which conduct commercial operations online can be exposed to normative constraints, which not only are counterintuitive to the idea of electronic commerce, but also superfluous, since the E-commerce Directive and the 2019/1150 Regulation offer enough guarantees for transparency and security in the provision of online services. Hence, the European Court of Justice’s intervention was needed in order to provide clarity and uniformity in the application of EU law.

This article has been prepared, for the Blog of the civil society of lawyers Costaș, Negru & Asociații, by atty. Miruna Mihuță from Arad Bar Association.

Costaș, Negru & Asociații is a civil society of lawyers with offices in Cluj-Napoca, Bucharest and Arad, which offers assistance, legal representation and consultancy in several areas of practice through a team composed of 20 lawyers and consultants. Details regarding legal services and team composition can be found on the website https://www.costas-negru.ro. All rights for the materials published on the company’s website and through social networks belong to Costaș, Negru & Asociații, their reproduction being permitted only for informational purposes and with correct and complete citation of the source.

[1] Directive 2000/31/EC of the European Parliament and of the Council of 8 June 2000 on certain legal aspects of information society services, in particular electronic commerce, in the Internal Market (‘Directive on electronic commerce or E-Commerce Directive’), Official Journal L 178, 17/07/2000.